WSU guest opinion: College is more valuable than ever

- Gavin Roberts

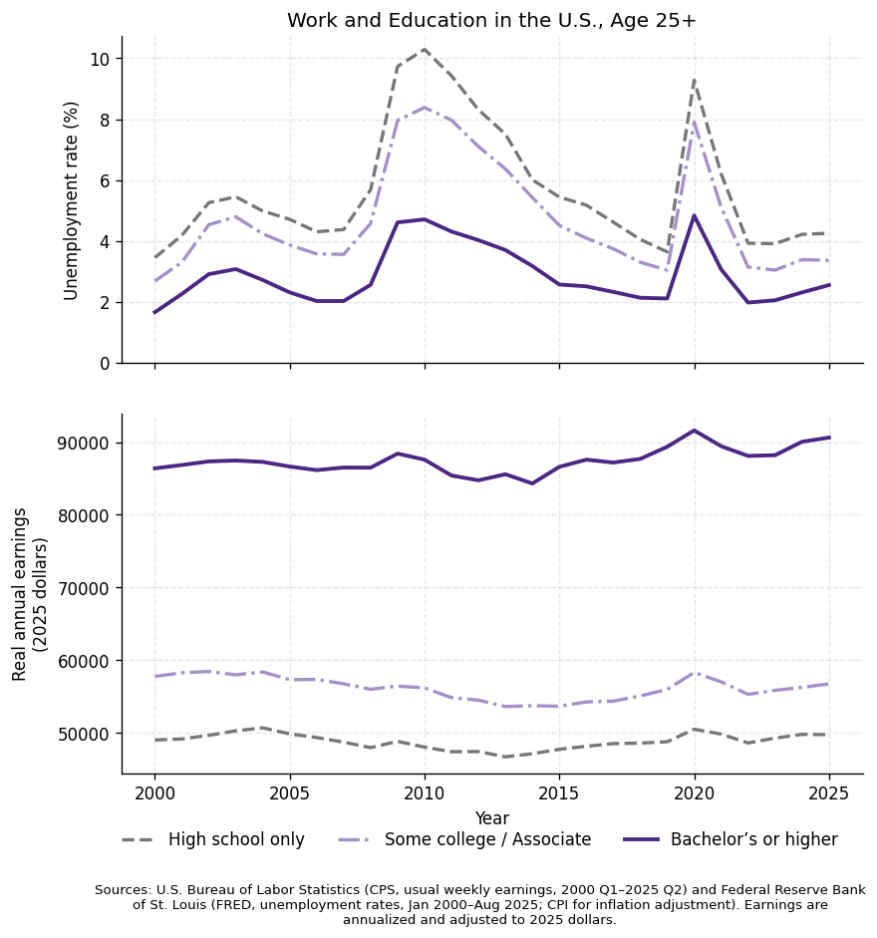

- Graphs showing unemployment and earnings by education.

Increasingly, Weber State University students wandering the halls of the Wattis Business Building or stopping by during office hours raise concerns about the declining value of a college education. A 2024 Pew survey found that only 22% of Americans agreed a four-year degree is “extremely or very important” for getting a good job, and a 2025 Gallup poll reported the perceived importance of college has fallen to its lowest level ever recorded. Add in news stories about stagnant wages for college jobs and artificial intelligence coming for white-collar work, and I sometimes catch myself thinking, in this world, what am I doing as a college educator?

At the same time, more and more Americans feel like they’re being left behind in an economy where technological progress accelerates faster than anyone can keep up. It becomes a mirage moving away just as you get close enough to grasp it. Many are not just imagining falling behind. Earnings for college-educated workers have pulled away in recent years, while workers with only a high school diploma have seen much smaller gains. Meanwhile, as a recent Wall Street Journal feature described, the ultra-rich increasingly live in insulated worlds of “extreme privacy,” complete with members-only restaurants, car-elevator condos, and six-figure bespoke wellness retreats. In a world so disjointed and stratified, no wonder people worry about falling behind.

I often revisit the data to search for reasons for hope. One trend has remained stable across every single year in the data since the turn of the century, through the tech bubble, the Great Recession, the pandemic, and everything that followed: People with more education consistently face lower unemployment and enjoy higher earnings. And in years when the economy faces headwinds, both gaps tend to widen, because in turbulent times, the knowledge and adaptability students pick up through critical thinking become more valuable.

But economic value is only half of what college offers. The other half is harder to measure, and maybe more important. In his famous “This is Water” commencement speech — I encourage you to look it up online — writer David Foster Wallace argued that the real purpose of a college education isn’t to tell students what to think, but to teach them what to pay attention to. In a noisy and distracted society, attention to important issues becomes increasingly scarce.

I see this every semester at Weber State. In the first few weeks of microeconomics, students are still warming up to the concepts of supply and demand and comparative advantage. Then something changes. A housing discussion breaks out about affordability in Ogden, zoning, shortages, and suddenly the concepts come alive. Or a conversation about the government shutdown and the fight over health care subsidies takes over the room, and students quickly begin connecting class to their own realities: How a funding lapse affects federal workers in Weber County, how hospitals respond when reimbursements shift, and how expanding support today often means adding debt that their generation will ultimately face.

And then their faces change. The moment when a student from Northern Utah realizes they can understand the world, not just react to it. They see that markets, incentives, and institutions aren’t mysteries reserved for experts in far-away cities but patterns they can interpret and evaluate themselves. It’s the moment they begin to grasp what the economist Friedrich Hayek meant when he wrote that “economic problems arise always and only in consequence of change.” They’re not memorizing formulas. They’re learning how to navigate a world that refuses to stand still. They learn the value of paying attention and of thinking critically about the changing forces that will shape the rest of their lives.

Some of these students will go on to become Federal Reserve vice presidents, Fortune 500 CEOs, professors at R1 universities, or even state senators — roles Weber State’s Goddard School of Business & Economics alumni already hold. But many will stay here in Weber County, running companies, shaping communities, serving in local and state government, or raising the next generation of Utahns. Wherever they go, they’ll carry something far more durable than a credential. They’ll carry an ability to read the economic landscape instead of being at its mercy.

Education doesn’t guarantee comfort; the chart makes that clear enough. But it does appear to offer more of it, if employment and income matter (they do). And beyond that, it gives people something even more important: agency. The ability to read the world instead of being pushed around by it. Wallace called that the real work of being human. For Weber State students, that work starts in Ogden, where understanding becomes the difference between drifting through life and directing it.

Gavin Roberts is an associate professor of economics and chair of the economics department at Weber State University. He is a recipient of the Gordon Tullock Prize from the Public Choice Society and regularly shares his research locally, nationally and internationally. This commentary is provided through a partnership with Weber State. The views expressed by the author do not necessarily represent the institutional values or positions of the university.